World War I and American Art: Part One

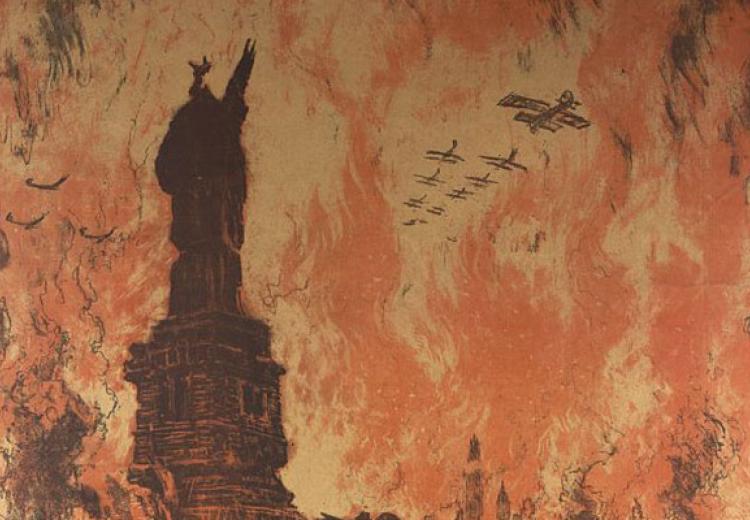

Joseph Pennell, “That liberty shall not perish from the earth," 1918.

World War I (1914-1918) has been called the seminal catastrophe of the twentieth century, leading to the destruction of four empires (Russian, German, Austrian-Hungrian, and Ottoman), the rise of communism and fascism, the Second World War, and even the Cold War.

Yet World War I is sometimes also called “America’s forgotten war.” Part of the reason for this is that the United States remained officially neutral until President Woodrow Wilson declared war in April 1917 and American troops did not arrive on European soil until June. Yet American wealth and power played an essential role in supporting the Allies and decisively defeating Germany. Moreover, unlike the other belligerent nations, the U.S. came out of the war more powerful in every respect than it entered.

The NEH-supported World War I and American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art is the first major exhibition to consider this global catastrophe from the eyes of American artists. With 150 works by 80 artists, it is likely to be the largest and most comprehensive such exhibition we will see in our lifetime.

As in every war, some artists were pro-war and others, opposed. Some changed positions as they learned more about the humanitarian crisis overseas. Some served in military, saw the horrors of war up close, and depicted it graphically. Some reflected wartime anxieties of the home front.

Walking through the rooms of the Academy, one is struck by how powerfully the paintings, watercolors, drawings, prints, and film on display grip the viewer. Because pictures have the advantage of immediate engagement, we thought to make these images more readily available for the classroom.

Cartoonist Winston McCay’s animated film The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918) took two years and 25,000 drawings, most of which were done by McCay. The fascinating backstory of the film can be accessed via Open Culture.The newspaper reports of the sinking are on Chronicling America.

One of the most heartrending scenes in the film is of a mother trying to keep her baby from drowning. Fred Spear’s 1915 poster Enlist depicts a mother and child as if asleep but now dead and sinking to the bottom of the ocean. The eloquence of the one-word title drives home the message: Enlist in the armed forces to help prevent further outrages to women and children!

Equally powerful is Joseph Pennell’s poster That Liberty Shall Not Perish from the Earth—Buy Liberty Bonds—Fourth Liberty Loan. The poster, part of a Liberty Bond campaign, presents an apocalyptic image of New York City under enemy attack, with a headless Statue of Liberty silhouetted against flames that engulf the city. Message: the U.S. is in peril if it does not put all its resources into the war effort. (Be prepared for comparisons with 9/11.)

At first glance, the flag paintings of American impressionist Childe Hassam seem to be in a different world than these posters. Hassam created his series of thirty paintings after being inspired by a “Preparedness Parade” that marched up Fifth Avenue in 1916. He was a strong supporter of American invention. These parades and the paintings were designed to evoke patriotic feelings in support of the Allies. Hassam was overjoyed when the U.S. entered the war, as we can see in his exuberant Allies Day, May 1917.

Beginning with American entry, artists tossed out an unprecedented number of posters aimed at motivating the public to participate in the war, whether by enlisting or by contributing actively to the aid of European and American troops. Appeals to moral indignation or shame were common as in Enlist - On Which Side of the Window Are You On?

On the other side of the political divide, left-wing artists such as John Sloan produced courageous and devastating illustrations such as After the War, a Medal and Maybe a Job for the radical magazine The Masses, critiquing America’s interventionist policies including conscription by evoking moral indignation for the pro-war business interests and compassion for its victims.

Another Masses contributor, the Ashcan painter George Bellows, initially took a strong pacifist antiwar stand. But after reading reports of the atrocities inflicted on civilians in Belgium, he produced an ambitious series of prints, drawings and monumental paintings. Taking Rembrandt’s Three Crosses along with Goya’s Disasters of War for his models, Bellows imagined the brutality and inhumanity of the German troops in Belgium. David Lubin, one of the curators of the exhibition, offers his thoughts on this series in the National Gallery Ashcan Goes to War podcast.

Next time, we’ll cover the artists who served on the front lines, either as soldiers, or as doctors, nurses and support staff. We’ll also look at the legacy of the war.