Afro Atlantic Art: Resistance and Activism

Alma Thomas, March on Washington, 1964

Courtesy National Gallery of Art

This resource, provided courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, presents a variety of artworks, from the 17th century to the present, that highlight the presence and experiences of Black communities across the Atlantic world (the relationships between people of the Americas, Africa, and Europe). Use the pieces in this collection to engage your students in conversation about the continuing fight for freedoms after abolition.

Find related artwork and activities in the EDSITEment Teacher's Guide Arts of the Afro Atlantic Diaspora.

Jacob Lawrence, Lou Stovall (printer), Toussaint at Ennery, 1989

Jacob Lawrence, Lou Stovall (printer), Toussaint at Ennery, 1989, color screenprint on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Alexander M. and Judith W. Laughlin, 1993.30.2

This screenprint by Jacob Lawrence is one of several works he made about the life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the revolutionary who led Haiti in pursuing independence from France and the abolition of slavery. In this scene, we see soldiers on horseback with long coats, blue hats, and swords hanging at their sides as they ride into battle. The blur of shapes and colors heightens the drama and intensity of the action.

In 1941, Lawrence became the first African American artist to have work in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Lawrence worked as a professor and artist for decades, and heroes of African American history like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and John Brown were among his most common subjects.

- What does this print tell you about Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution?

- What new emotions or perspectives does Lawrence bring to the event?

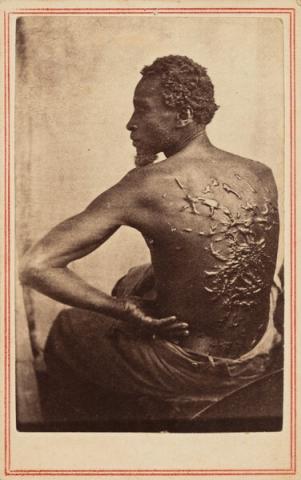

McPherson & Oliver, The Scourged Back, c. 1863

McPherson & Oliver, The Scourged Back, c. 1863, albumen print (carte-de-visite), National Gallery of Art, Washington, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2018.95.2

McPherson & Oliver were photographer partners who documented the impacts of the Civil War in Louisiana. This photograph, their best-known image, shows the scars from whipping on the back of a formerly enslaved man widely known as Gordon. It was made in a camp of Union soldiers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where the subject had taken refuge after escaping his bondage on a nearby Mississippi plantation.

A reproduction of this image was published in a special Independence Day edition of Harper’s Weekly with an account of Gordon’s escape. The photograph also circulated as a carte-de-visite, a small and sturdy format popular in the 19th century that allowed photographs to be easily mailed and transported. The circulation of Gordon’s portrait rallied support and raised funds for abolition and the Union.

- What feelings does this image raise for you?

- Do you think this photograph functions as a work of activism? Why or why not?

- How is art or photography used to persuade viewers on important topics today?

Alma Thomas, March on Washington, 1964

Alma Thomas, March on Washington, 1964, acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York

On August 28, 1963, Alma Thomas and her friend Lillian Evans, both of whom were in their 70s, met with congregations of local churches and strode arm in arm to join the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a famed demonstration for racial equality and civil rights where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Thomas, whose family moved from Columbus, Georgia, to Washington, DC, in 1907, lived in the District for most of her life, as an educator and artist. She developed a distinctive abstract style of painting, and her art was typically not explicitly political. In this painting, she captures the energy of the diverse crowd, holding enormous signs of protest, highlighted with splashes of red and yellow.

- How do you think it felt to participate in the March on Washington?

- Why do you think Thomas might have chosen to paint this event?

- Watch a 1963 video documenting the March on Washington. How does this painting compare to scenes from the event?

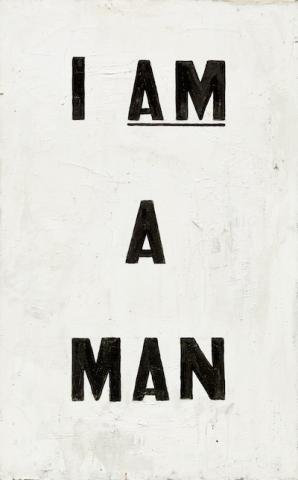

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988, oil and enamel on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund and Gift of the Artist, 2012.109.1

Untitled (I Am a Man) is a representation of actual signs carried by more than 1,300 African American sanitation workers on strike in Memphis in 1968. Prompted by the wrongful deaths of two coworkers from faulty equipment, the strikers—joined by Martin Luther King Jr.—marched to protest low wages and unsafe working conditions. They took up the slogan “I Am a Man,” a variant on the first line of Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1952): “I am an invisible man.” This slogan and these signs were used throughout the civil rights movement of the 1960s and continue to be used today.

In this work, Ligon differentiates his painting from the original, historical signs by reorganizing the line breaks and painting the black letters in eye-catching enamel. In 1988, the same year Ligon completed this painting, the Civil Rights Restoration Act was passed, expanding non-discrimination requirements for groups receiving federal funding.

- Why do you think the word invisible was removed from the Ellison line to create this slogan?

- Do you think this artwork acts as a form of protest? Why or why not?

This resource is drawn from the content of the Afro-Atlantic Histories exhibition organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, Washington. All related materials found on EDSITEment have been provided courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.