Arthur Miller’s The Crucible: Witch Hunting for the Classroom

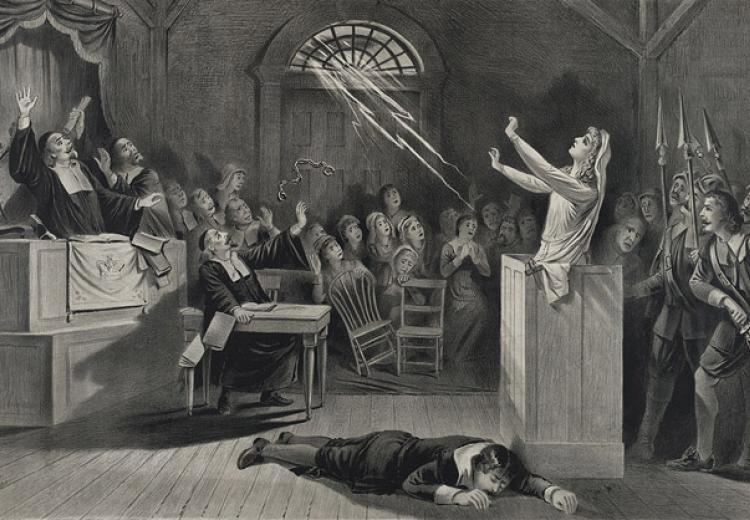

A bolt of lightning releases the handcuffs on a woman accused of being a witch and strikes down her inquisitor in this late nineteenth-century lithograph of a colonial-era trial.

"It would probably never have occurred to me to write a play about the Salem witch trials of 1692 had I not seen some astonishing correspondences with that calamity in the America of the late 40s and early 50s. My basic need was to respond to a phenomenon which, with only small exaggeration, one could say paralyzed a whole generation and in a short time dried up the habits of trust and toleration in public discourse."

—Arthur Miller

In their book Salem Possessed, Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum remark upon the prominent place the Salem witch trials have in America's cultural consciousness. They observe, “For most Americans the episode ranks in familiarity somewhere between Plymouth Rock and Custer's last stand.” Moreover, they note that because of the trials' dramatic elements, “It is no coincidence that the Salem witch trials are best known today through the work of a playwright, not a historian ... When Arthur Miller published The Crucible in the early 1950s, he simply outdid the historians at their own game.”

The Crucible and the Salem witch trials

EDSITEment lesson Dramatizing History in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, offers an engaging series of activities for students to examine the ways in which Miller interpreted the facts of the witch trials and successfully dramatized them. Aligns with CCSS RL.11-12.3 - Analyze the impact of the author’s choices regarding how to develop and relate elements of a story or drama.

Scrutiny of Miller's historical sources, which include biographies of key players (the accused and the accusers) and primary source transcripts of the Salem witch trials themselves give students a chance to trace the events embellished in the play back to historical Salem. A detailed study of a timeline accompanies their close reading of The Crucible. Students put themselves in the place of the playwright to answer:

- What makes these trials so compelling?

- What is it about this particular tragic segment of American history that appeals to the creative imagination?

- How can history be dramatic, and how can drama bring history to life?

Aligns with CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.3 - Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

As students examine historical materials with an eye to their dramatic potential, they also explore the psychological and sociological questions that so fascinated Miller:

- Why were the leaders of Salem's clerical and civil community ready to condemn to death 19 people who refused to acknowledge being witches based on spectral evidence and the hysterical words of young girls?

- Why would the church and government authorities continue to credit these wild and unsubstantiated stories as respectable people from all walks of life—landowners, women of independent means, neighbors, even clergy—were arrested and brought to trial?

- What was it about the time period that made such hysteria, and ultimately tragedy, possible?

Aligns with CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.8 - Evaluate an author's premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information.

An additional activity would be to ask students to compare two or more recorded or live productions of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible to the written text. They may evaluate how each version interprets the source text and debate which aspects of the enacted interpretations of the play best capture a particular character, scene, or theme.

Aligns with CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.7 - Analyze multiple interpretations of a story, drama, or poem (e.g., recorded or live production of a play or recorded novel or poetry), evaluating how each version interprets the source text. (Include at least one play by an American dramatist.)

The McCarthyism connection

Many teachers use The Crucible alongside their discussion of McCarthyism. Indeed, Miller uses witchcraft and the Salem witch trials as a metaphor for situations wherein those who are in power accuse those who challenge them of suspect behavior in order to destroy them. Salem is an early example of what Miller saw around him and personally experienced in the 1950s—the communist witch hunts conducted by Senator Joseph McCarthy.

One interesting connection would be to teach the play along with a film that is very much about McCarthyism—John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Students can make very profitable comparisons between the two tragic heroes: The Manchurian Candidate’s Staff Sergeant Raymond Shaw, and The Crucible's John Proctor.

Another approach would be to have students read and analyze the following informational text by Miller, which recollects his personal experience with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956 when he refused to “name names.” Miller was convicted June 1, 1957 for contempt of Congress. His 17 June 2000 article in The Guardian/The Observer, "Are You Now Or Were You Ever?," describes the paranoia that swept America in that era— and the moment his then-wife, Marilyn Monroe, became a bargaining chip in his own prosecution.

Aligns with CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.11-12.5 - Analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of the structure an author uses in his or her exposition or argument, including whether the structure makes points clear, convincing, and engaging.

Miller sums up his experience with the benefit of hindsight:

"I am glad that I managed to write The Crucible, but looking back I have often wished I'd had the temperament to do an absurd comedy, which is what the situation deserved. Now, after more than three-quarters of a century of fascination with the great snake of political and social developments, I can see more than a few occasions when we were confronted by the same sensation of having stepped into another age."