George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and the Presidents' Day holiday

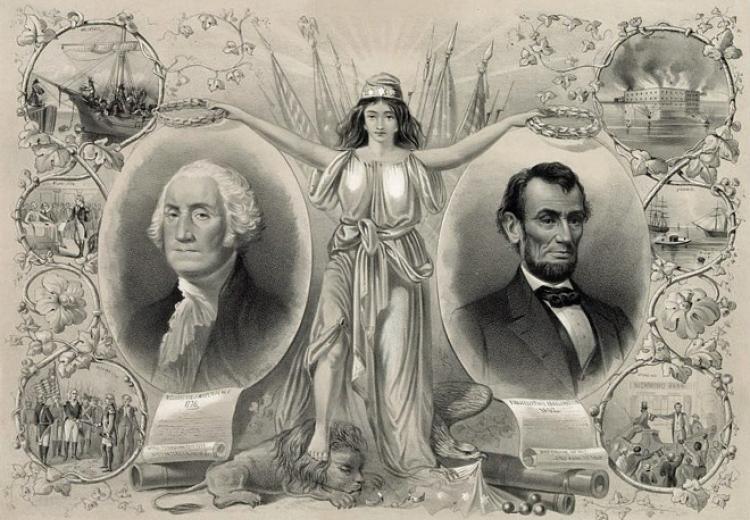

Kimmel & Forster, Columbia's Noblest Sons, c. 1865.

Between the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12) and George Washington (February 22), our commercial republic* has come to celebrate a national holiday unofficially called “Presidents' Day” (February 16), which generically honors all the presidents. Washington and Lincoln stand out as unrivaled figures in American history. Their importance is reflected in the large number of lessons about them in our collection.

In this special post we look at the history of this holiday, discuss how the long-weekend became a permanent fixture on the work and school calendars with passage of the Uniform Monday Holiday Act in 1968, and provide a collection of lessons and resources about the chief executives of the United States.

Establishing Presidents' Day

A long weekend in the middle of February is perhaps the first thing that comes to mind at the mention of Presidents’ Day. But consensus about the delight that is a Monday off of school or work (for those fortunate enough to get the day off) is where the agreement surrounding Presidents’ Day begins to break down.

In fact, the official federal holiday celebrated on the third Monday of February isn’t even called Presidents’ Day: it’s Washington’s Birthday. Until the 1970s, the holiday was celebrated on Washington’s actual birthday, February 22nd (if you want to get really specific, Washington was born on February 11, 1732, but because the British colonies switched from the Julian to Gregorian calendar in 1752, his birthday was bumped 11 days to February 22nd).

People celebrated Washington’s birthday long before Congress declared it an official holiday in 1879, and continued to celebrate on February 22nd for almost a century. In 1968, however, Congress sought to provide tourist and retail industries with more lucrative long weekends by shifting several federal holidays—like Memorial Day and Labor Day—to Monday with Public Law 90-363, known as the Uniform Monday Holiday Act. Washington’s Birthday was among those holidays that were affected, so once again, his birthday was moved. This time, however, it was not connected to a specific date but instead attached to the third Monday in February.

This decision was not without controversy. Changing the calendar was a chance to rethink not only when public holidays would take place, but also who was commemorated. Illinois representative Robert McClory wanted the holiday to celebrate Abraham Lincoln, his own state’s native son, whose birthday conveniently fell on February 12th. McClory’s campaign to change the name of the holiday to “Presidents’ Day,” in honor of both men, was unsuccessful (as was his interest in making April 2nd a federal holiday to honor Thomas Jefferson's birthday). However, by pushing for the holiday to take place on the third Monday in February, McClory (perhaps inadvertently) ensured that Washington’s Birthday would never be celebrated on Washington’s birthday: February 22nd never falls on the third Monday of the month.

All of this congressional debate, of course, took place at the federal level. States could—and did—establish their own holidays in honor of Washington, Lincoln, and presidents in general. At the national level, as historian C.L. Arbelbide recounts, it was advertisers who transformed Washington’s Birthday into Presidents’ Day, finding the long weekend a perfect occasion to market travel deals, cars, pianos, clothing—pretty much anything. Through Chronicling America, you'll find advertisements for discount shopping to honor Washington's birthday in newspapers such as the February 20, 1901 edition of Evening World and reduced prices on home appliances available at Sears and Roebuck in the February 21, 1949 edition of the Evening Star.

Public holidays are one way people have tried to draw links between past and present, and even their meanings—as the case of Washington’s Birthday illustrates—are not stable over time. Many have lamented this instability: representatives who opposed moving Washington’s Birthday to a Monday feared that young people would “not know or care when Washington was born,” and, by extension, what his significance was. It’s probably the case that the separation of Washington’s birthday and Washington’s Birthday, coupled with the commercialization of the holiday, has meant that less attention is paid to the original reason for the holiday. The developments surrounding the holiday and our relationship to history, however, also means that Washington’s Birthday (or Presidents’ Day) can become an occasion for a more nuanced and thoughtful reflection on the legacy of the first president and all those who have followed.

George Washington

EDSITEment has a rich array of lesson plans on Washington, beginning with his earliest exploits as a solider and general. What Made George Washington a Good Military Leader? focuses on the military and political virtues that emerged during Washington's long service to his country in the French and Indian Wars and the Revolution. Washington lost many battles but won the war. His ability to turn a military defeat into inspiring lessons for his troops made men follow him into battle. When he laid down his command of the army at the peak of his success and retired to his beloved Mt. Vernon, he astonished America and the whole European world.

Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention. The men who drafted the Constitution had his honorable example before them as they drafted Article Two, which sets forth the powers and responsibilities of the office of presidency. His support for the document helped secure passage in the state ratifying conventions. With some misgivings about the costs to his peace of mind and reputation, yet compelled by his sense of duty, Washington agreed to serve as president. His eight years in office set the precedent for all future occupants.

Abraham Lincoln

Like many ambitious young men before him, Abraham Lincoln began his political career with praise for George Washington. Yet after one unsatisfying term in Congress he return to Illinois to become a successful lawyer. Passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1852) altered the political balance between free and slave states and drove him from his comfortable and lucrative practice back into national politics. In Abraham Lincoln, the 1860 Election, and the Future of American Slavery, students can examine the arguments Lincoln made to justify his claim to lead the Union as president.

The decision-making process that precipitated the Civil War is a fascinating subject and the focus of Lincoln Goes to War. In this lesson, students examine the deliberations within the Lincoln administration that led to the defense of Fort Sumter from Confederate attack in April 1861.

While armies clashed on battlefields from Pennsylvania to Louisiana, partisan politics continued in Washington, D.C. Congress—as well as the nation at large—hotly debated issues related to the president's handling of the war. Abraham Lincoln and Wartime Politics examines the controversies arising from Lincoln’s role as a wartime president and asks students to argue whether he deserved a second term.

Students can examine the result that the stresses and strains of this conflict had on Lincoln by examining Alexander Gardner’s photograph of the president, taken a few months before his assassination. Gardner’s famous photograph is part of the EDSITEment lesson, Picture Lincoln, which is built around the rich significance of this image. Our Closer Reading on Lincoln's Enduring Legacy begins with his presidency, the events surrounding his assassination, and traces the short and long-term effects of his presidency.

A Word Fitly Spoken: Abraham Lincoln on Union explores this rich vein of political reflections on the subject of American national union. By examining Lincoln's three most famous speeches: the Gettysburg Address; the First and Second Inaugural Addresses; and a little-known fragment on the Constitution, union, and liberty, students trace what these documents say regarding the importance of the Union for the future of republican self-government.

EDSITEment Resources

The following lessons for grades K-12 are about the office of the presidency, with primary sources, video and audio media, and activities for research and small group discussion included.

The President's Roles and Responsibilities: Communicating with the President (grades K-5): Through these lessons, students learn about the roles and responsibilities of the U.S. president and their own roles as citizens of a democracy. A similar set of lessons are available and tailored for grades 6-8.

Presidential Inaugurations: I Do Solemnly Swear (grades K-5): Help your students reflect on what the Presidential inauguration has become and what it has been, while they meet a host of memorable historical figures and uncover a sense of America's past through archival materials.

Like Father, Like Son: Presidential Families (grades K-5): This lesson provides an opportunity for students to learn about and discuss two U.S. families in which both the father and son became President.

Before and Beyond the Constitution: What Should a President Do? (grades 6-8): In this curriculum unit, students look at the role of President as defined in the Constitution and consider the precedent-setting accomplishments of George Washington.

Who was Really Our First President? A Lost Hero (grades 6-8): In this sequence of lessons, students look at the role of President as defined in the Articles of Confederation and consider the precedent-setting accomplishments of John Hanson, the first full-term “President of the United States in Congress Assembled.”

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 (grades 9-12): In this unit, students will examine the roles that key American founders played in creating the Constitution, and the challenges they faced in the process. They will become familiar with the main issues that divided delegates at the Convention, particularly the questions of representation in Congress and the office of the presidency.

James Madison: From Father of the Constitution to President (grades 9-12): In this curriculum unit, Madison's words will help students understand the constitutional issues involved in some controversies that arose during Madison's presidency.

The Presidential Election of 1824: The Election is in the House (grades 9-12): In this unit, students will read an account of the election from the Journal of the House of Representatives, analyze archival campaign materials, and use an interactive online activity to develop a better understanding of the election of 1824 and its significance.

Resources for Presidential History

Produced by the Texas Humanities Council, Humanities Texas, A President’s Vision is an attractive set of U.S. history resources that examine the aspirations of seven notable U.S. presidents through the programs and initiatives that advanced each man’s vision. The centerpiece of the program is a series of seven digital interactive posters examining the leadership and policies that shaped the presidencies of Washington and Lincoln along with those of Thomas Jefferson, Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, Lyndon Baines Johnson, and Ronald Reagan.

This Smithsonian video walks you through the Hall of Presidents at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Mount Vernon has a collection of online exhibits about the lives of enslaved people on Washington’s plantation. The site also has resources discussing Washington’s relationship with Native Americans.

For anyone who wants to learn more about 20th-century presidents, Ken Burns The Roosevelts and the American Experience series The Presidents are highly recommended.

*The idea of a modern commercial republic—large, dynamic, and liberal—as being superior to the ancient military republics of Greece and Rome was first argued by Montesquieu in the Spirit of the Laws. This argument was further supported by David Hume, elaborated by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, and underlies the arguments in favor of the U.S. Constitution in the Federalist Papers.