The Gift of Holiday Traditions: Kwanzaa, Hanukkah, and Christmas

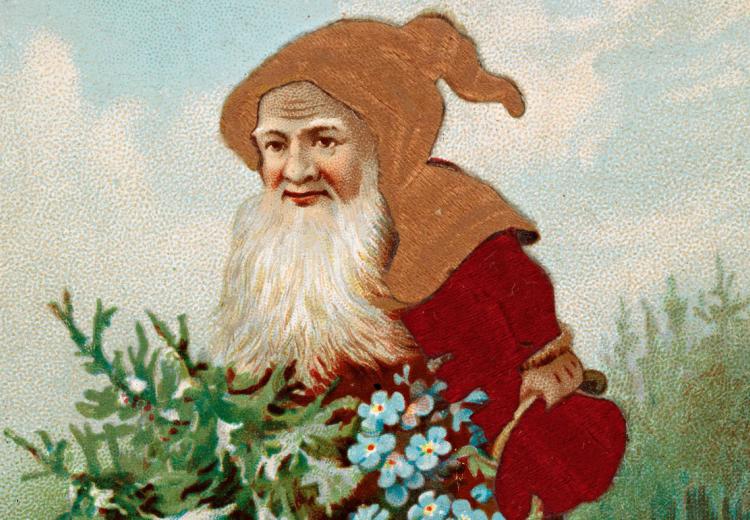

"Nisse on Christmas Card" (Norway, 1885).

"Happy, happy Christmas, that can win us back to the delusions of our childhood days, recall to the old man the pleasures of his youth, and transport the traveler back to his own fireside and quiet home!"

— Charles Dickens

Each year, December brings a month filled with holidays, celebrations complete with a variety of gift giving traditions, and—to the glee of students and educators alike—school vacations. Before departing to enjoy the break from school, take the opportunity to discuss with students ritual gift giving in their own families and across cultural holiday traditions. Some questions to have them consider:

- How do individual families customize their holiday celebrations with gift exchanges and other rituals?

- In what ways does holiday gift giving figure in the popular imagination through great literature that is re-read and performed year after year?

- Trace holiday traditions especially the practice of gift giving as it unfolds over time and consider if common themes and elements can be found within different spiritual traditions.

Activity

To prepare your students to explore ways the holidays have evolved over time, teachers and parents might begin with this simple exercise, appropriate for students of all ages:

Have the student pick a favorite family holiday. Ask them to interview various family members—especially parents and grandparents—about their favorite traditions both now and when they were children, including ways in which family members handle gift giving.

Questions may include which activities still form part of their family holiday traditions, and which are no longer done. Lead students in an investigation of why certain traditions ended and others began and what the significance of giving gifts in their families is. Students might conclude by writing a brief essay about their family gift giving and other holiday traditions, old and new, including those lost or recently added.

Gift Giving

Of course, some curmudgeons do not feel any pressure to shop for gifts at all. Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol was first published in 1843, and popularized “humbug” for holiday scrooges everywhere. On a certain fateful Christmas Eve, Ebenezer Scrooge watches his past, present, and future life from an outside perspective while being accompanied by three ghosts and wakes to experience a change of heart and being. Explore this enduring holiday classic about redemption and family with a new resource: Using Textual Clues to Understand “A Christmas Carol” (3 Lessons). In Lesson 1, students focus on the first stave of the novel as they identify the meanings of words and phrases that may be unfamiliar to them. This activity facilitates close examination of and immersion in the text and leads to an understanding of Scrooge before his ghostly experiences. In Lesson 2, students examine Scrooge’s experiences with the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future and discover how Dickens used both direct and indirect characterization to create a protagonist who is more than just a stereotype. In Lesson 3, students focus on stave 5 as they identify and articulate themes that permeate the story.

Was A Christmas Carol the only story Charles Dickens wrote about the holiday season? Read the HUMANITIES magazine article A Christmas Carol Was Not His Best Holiday Novel, Charles Dickens Thought to learn more about Dickens, holiday ghost stories in England, and connections between literature and Christmas traditions in the United States.

Dickens’s Scrooge is not the only literary figure to experience an epiphany on Christmas Eve. "Twas the night before Christmas and all through the house, not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse” opens one of the most famous poems about Christmas, "A Visit from St. Nicholas." (An e-text of the poem, with illustrations, is available through Project Gutenberg.) Professor Clement C. Moore came forward to claim authorship of "A Visit from St Nicholas" in 1844; however, some evidence indicates that it may have been the work of Major Henry Livingston, Jr. EDSITEment-reviewed American’s Story from America’s Library contains a brief feature on this staple holiday chestnut, which helped establish the image of a magical gift-bearing Santa figure into the national consciousness of America. See "Washington Irving: Author of America's Christmas" for a discussion about how this author conjured up an earlier prototype of our modern-day jovial Santa Claus who soars through the night sky, landing on rooftops to deliver presents (via chimneys) to good girls and boys.

From holiday literature, we turn to the many holiday gift-giving traditions that emanate from a combination of religious and secular celebrations and customs. In gift giving between family and friends, students may find a common thread running across cultures/religions throughout December holidays, including Kwanzaa, Hanukkah, and Christmas.

Kwanzaa

The History of Kwanzaa provides an extensive history of this secular holiday, which is celebrated from December 26th until New Year’s Day. For each of seven days, celebrants recognize a principle or value (Nguzo Saba), for example, Unity or Self Determination. Each day is also associated with a symbol, such as Mazao, crops that “symbolize work and the basis of the holiday” or Zawadi, which are “meaningful gifts to encourage growth, self-determination, achievement, and success.” Kwanzaa itself is a word adapted from a Swahili phrase for “first fruits.”

After the Watts riots in Los Angeles in 1966, the idea for Kwanzaa as a Pan-African holiday was created by activist Dr. Maulana Karenga as he searched for ways to bring African Americans together within families and as a community. In his research into African "first fruit" (harvest) celebrations, Karenga combined aspects of several different African traditions, such as those of the Ashanti and Zulu, to form the basis of Kwanzaa.

The last day of Kwanzaa, or Imani, focuses on gift giving as a means to honor the creative spirit and reaffirm self worth. Therefore, the gifts are often homemade rather than purchased. However, the essence of Kwanzaa does not lie in exchanging presents, but in commemorating a shared heritage. Togetherness is emphasized as family and friends come together through this special time to align themselves with the guided principles.

Kwanzaa has been embraced across cultural and racial divides to become not only a wonderful celebration of family and culture, but also a fabulous example of how holidays develop through the creative combination of historical circumstances, cultural antecedents, and creative thinking.

Hanukkah

In learning about Kwanzaa, students will recognize the symbolism and shared values that are at the heart of all winter holidays. Hanukkah, celebrated in Jewish communities from Paris to Syria and Boston to St. Louis, is another example. In this holiday, families can come together to light the menorah candles and exchange gifts for each of the holiday’s eight nights.

Hanukkah celebrates a miracle that occurred after the Jewish people reclaimed their temple from their Seleucid (Macedonian) conquerors. Refusing to worship the empire’s Greek deities, the Jews rebelled and eventually won back their temple after a three-year war. As part of the celebration, the victors wanted to light the Menorah but had only a single day’s worth of oil available. The oil, however, lasted for eight days, leading to the eight-day celebration of Hanukkah, known also as "The Festival of Lights." The History of Hanukkah puts the holiday in its historical context and includes descriptions of some traditions, such as playing the dreidel, a four sided top.

The dreidel game was popular during the rule of the Seleucid emperor, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who reigned before the Maccabean revolt of 166 BCE. This was a time when soldiers executed any Jews who were caught practicing their religion. When pious Jews gathered to study the Torah, they prepared the top in case they heard soldiers approaching. If the soldiers appeared, they would hide the holy scriptures and pretend to play with the dreidel. To play the game in the classroom or at home, students may want to reference the rules of the game.

Gift giving, another tradition of Hanukkah, has continued to grow in popularity over the years. The act of exchanging presents between family members and friends is a relatively new practice that evolved out of the modest monetary present (gelt-giving) that 17th or 18th-century eastern European Jews bestowed on religious teachers around the time of this holiday. By the 19th-century, the gifts had been transferred to children. The arrival of chocolate gelt (Yiddish for money) took place in the 1920s, and was perhaps based on the chocolate money that Dutch children received from Sinterklaas. The gift-giving tradition is no longer reserved to coin distribution for children but extends to different forms of gifts and now included adults. In present-day America, gelt can take the form of candy or substantial gifts of money placed inside a card for the lucky recipient.

As with the modern celebration of Christmas, the relatively new addition of gift giving to this traditional celebration serves to bring people close to each other during the darkest time of the year. For further discussion of this theme listen to Naughty & Nice: A History of The Holiday Season, from Back Story with the American History Guys, which examines the history of the holiday season and how December holidays have changed over the years. Part of the program concerns how the American Jewish community has shaped and reshaped the Hanukkah celebration.

Christmas

The holiday that celebrates the nativity of Christ, is as diverse as the many countries that observe it, and was a popular subject in the Catholic and Orthodox religious art of the middle ages and Renaissance. (See the EDSITEment-reviewed Metropolitan Museum of Art's presentation of the Christmas Story in Art, for examples). While the actual date of Christ’s birth is disputable, it has been suggested that December 25th was a Christian replacement for pagan and polytheistic rituals related to the winter solstice. The History of Christmas gives historical context to this holiday, including its mixed origins. Excerpts from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah, an enduringly popular musical work often played at Christmas shaped by the King James Bible, can be found at NEH funded online exhibition, Manifold Greatness.

For the ancient Romans, the winter solstice was a time of the Saturnalia festival, marked by gift giving and revelry, as well as bonfires and a practice of topsy-turvy role reversals between master and servants. Like Kwanzaa, Saturnalia centered on giving thanks for the fruits of the earth and plentiful crops that would ensure continued prosperity in the coming year. Business transactions were forbidden and relaxation was the watchword for servants as well as masters. The Romans had a tradition of exchanging ceramic dolls called sigillaria, which they hung on the branches of evergreen trees. Similarity has been drawn between the pointed felt hats worn by department store Santas and a brimless hat, called a pileus, worn by the Romans during this festival.

In Northern European folklore, the twelve days between Christmas and the Feast of the Epiphany (January 5th) were thought to be a time when evil spirits were especially active. To combat these forces as well as celebrate the victory of light over winter darkness, people would go out to the woods to gather evergreen plants and trees such as pine, ivy, and holly and decorate their homes with them along with all manner of lights. The practice of putting up a Christmas tree seems to be of rather recent in origin, as late as the 16th century. It originates with the Germans who began to bring small fir trees into their households and ornament them with fruit, tinsel, and small candles.

In a similar way, the Yule log was kindled on Christmas Eve in northern countries and was kept burning through Twelfth night. The Yule log is a remnant of the bonfires that were lit by pre-Christian people during the winter solstice to symbolize the return of the sun. It was traditional to retain a small piece of unburnt Yule log to kindle next year’s Yule fire. This annual ritual lighting was intended to guarantee prosperity in the coming year, extending from the whole cosmos to the natural world to the family circle.

No bearer of goodies and gifts is more recognizable in the popular imagination than that jolly old fellow, Saint Nick, accompanied by his trusty elves and reindeer. With little more thanks than the requisite glass of milk with cookies, and carrot for Rudolph, Santa magically transcends space and time delivering presents to all the good children of the world. The character Santa Clause and his precursor, St. Nick, symbolize the underlying theme of generosity during the holiday season. Students may explore further the distinction between Santa and Saint Nicholas as they Discover the Truth About Santa Claus.

Santa Claus and other Christmas traditions such as the Christmas tree, as we know them in the United States, were created through a compilation of legends and customs from around the world. What They Left Behind: Early Multi-National Influences in the United States has students explore the European influences on the development of all aspects of America, including a song about “Sinter Klaas” from the Netherlands. Younger students learning the history and culture of Christmas celebrations may want to visit the brief history of Christmas at America’s Story, a part of America's Story from America's Library.

Featured Lessons

Featured Websites

- A Victorian Christmas

- Ancient Origins

- Christmas History and Christmas Traditions

- Discover the Truth About Santa Claus

- History Channel Exhibit on Kwanzaa

- History Channel Exhibit on Hanukkah

- History Channel Exhibit on Christmas

- How to Play Dreidel

- Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture

- America’s Story

- Back Story with the American History Guys

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Victorian Web