Women’s History through Chronicling America

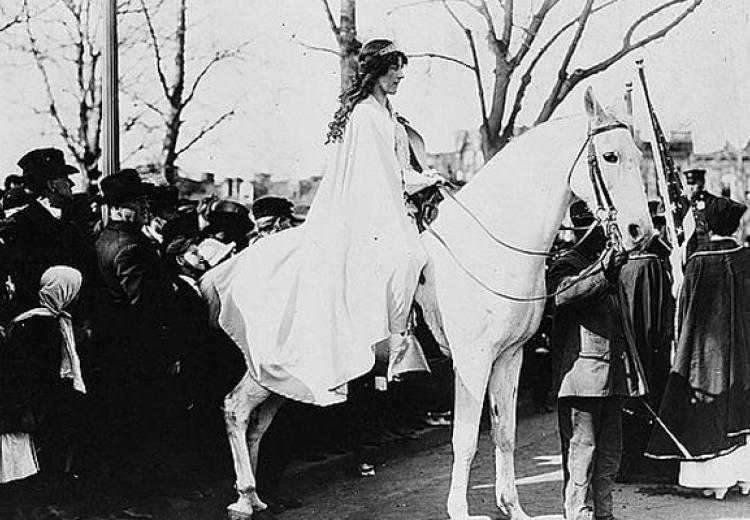

National American Woman Suffrage Association Parade, 1913

Chronicling America, a collaborative project of NEH and the Library of Congress, offers a deep repository of historic American newspapers covering the years 1836–1922. Students can use newspapers available through Chronicling America to expose the rich texture of the women’s rights movement and its many milestones, meetings, and debates right from the beginning and in a way that few other resources can. As an added bonus, they will be working with the kind of complex informational texts that the Common Core English Language Standards recommends. In what follows, we'll be suggesting articles written from a variety of points of view that make arguments based on appeals to evidence.

Seneca Falls Convention

Let’s begin with the coverage of early women’s rights advocates, including Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who planned a two-day convention in Seneca Falls, New York, to discuss women’s role in society in July 1848.

Convention attendees boldly prepared a “Declaration of Sentiments,” modeled on the Declaration of Independence, delineating the “civil, social, political, and religious rights” of women. After some debate, delegates decided to also include in the declaration women’s suffrage the right to vote. Some observers at the time were quite dismissive of the convention. A write-up in the Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania Jeffersonian Republican reported that:

The women of Seneca Falls had a convention at which they put forth a “declaration of independence” asserting that men and women were created equal. This being a leap year, the women have a perfect right to make “declarations” of any descriptions without impunity.

Despite such mocking, the organizers held similar meetings over the next two years in Rochester, New York, and in Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. Many years later, a New York newspaper article reporting on the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, pointed to the foundation for women’s rights laid at Seneca Falls.

The West advances the right to vote

Yet, it was not in the East but in the West where women first gained voting rights. Contemporary observers attributed the early adoption of women’s suffrage in the western states to various factors, including the unconventional personalities of those who settled there, the need to attract women to an area populated primarily by men, or simply a ploy to solidify power by expanding the voter base.

In 1890, Wyoming was the first state to grant women full suffrage, followed in quick succession by Colorado, Utah, and Idaho. In Utah, the Evening Dispatch proclaimed that women’s suffrage “went into the constitution with a whoop.”

Soon newspapers were debating the effects. An 1894 article in the Kansas Agitator entitled “Wyoming Leads in Morals,” suggested that, because women in Wyoming had the right to vote, the state had a smaller ratio of criminals in the population than the “supposedly most civilized” northeastern states.” According to the article, Wyoming’s improvement from its roots as “the most barbarous and murderous [place] on the continent” stemmed from the civilizing influence of women’s participation in public affairs. “The air of liberty,” stated the article, “breeds purity.”

The Reform Movement

In the West as in the East, the mouthpiece for hashing out issues involving women’s rights was found in the local press, in which women took an active role. For example, until the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act of 1878, married women in Oregon had no property rights, and any wages women earned legally belonged to their husbands.

Abigail Scott Duniway, known as “Oregon’s Mother of Equal Suffrage,” published The New Northwest in Portland from 1871 to 1887. Like many suffragists, Duniway advocated reforms beyond women’s enfranchisement, including temperance, wage equality, the right of women to own property, and the rights of Native Americans and Chinese immigrants. The New Northwest was “a journal for the people … not a women’s rights, but a human rights organ, devoted to whatever policy may be necessary to secure the greatest good for the greatest number.” One of its earliest battles was for economic rights for women. In 1912, when Oregon became the seventh state to grant women suffrage, the state’s governor asked Duniway to draft and sign the equal suffrage proclamation.

Temperance

From the beginning, women’s suffrage was closely connected with the movement for temperance and intertwined in the public discussion of women’s rights. For some observers, this connection was natural. Alice Stone Blackwell, a prominent journal editor, defended suffrage on many grounds, observing that it would increase the amount of “dry” territory in the United States and reduce the “power of the saloon in politics.” On the other hand, a critical article in the Ogden [Utah] Standard asked, “Is Woman’s Suffrage Throwing John Barleycorn?” and sought to separate the demand for suffrage from the prohibition of alcohol, pointing out that the earliest states to adopt woman suffrage, Wyoming and Utah, had not become dry decades after women got the right to vote there.

The Antis

As the women’s rights movement gained momentum, so did opposition. The New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, founded in 1897, asked “Why force women to vote?”

About the author

Mary Downs and Leah Weinryb Grohsgal are NEH Program Officers in the Division of Preservation and Access.