Walden, a game

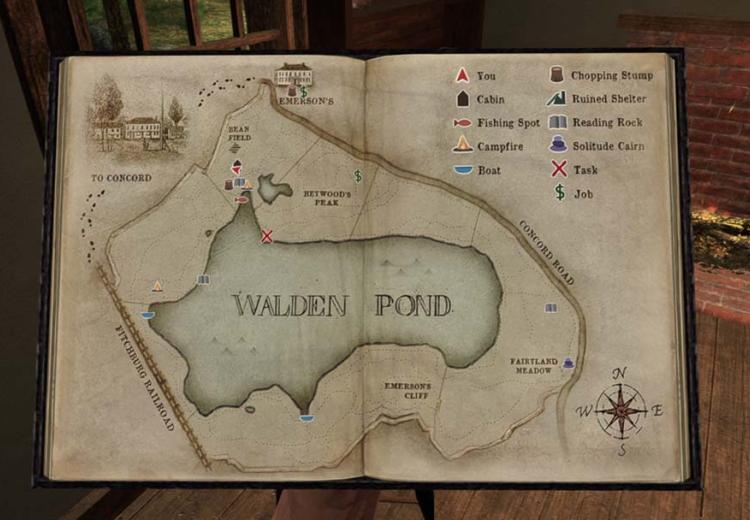

Map of Walden Pond as depicted in Walden, a game

To walk in a winter morning in a wood where these birds abounded, their native woods, and hear the wild cockerels crow in the trees, clear and shrill for miles over the resounding earth, drowning the feebler notes of other birds—think of it!

—Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s classic meditation on self-reliance and nature, continues to offer students a valuable perspective nearly two centuries after its first publication in 1854. Now students can also experience the world of Walden Pond through a role-playing game funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Walden, a game lets students explore the woods where this transcendentalist thinker made his temporary home, and a new suite of supporting classroom materials helps teachers bring the experience into their English language arts or social studies curriculum.

In this game, players assume the role of Henry David Thoreau as he carries out his experiment of self-reliance and searching for the sublime in nature. The narrative of Thoreau’s first year in the woods loosely guides the play, which offers reflective practice rather than strategy or competition.

By simulating the experience of Thoreau – building a cabin in the woods, keeping a journal, interacting with nature and animals – students gain an appreciation for the transcendentalist philosophy at the heart of Walden. The Walden Woods Project, with support from NEH, has made available the full text of Walden, as well as correspondence and many other archival resources you may find helpful.