EDSITEment, NEH's website that helps teachers bring online resources into the classroom, provides a number of lesson plans and reviewed websites that help you commemorate Constitution Day with your students. Listed here is a lesson plan for each grade band that can help you bring the Constitution into your classroom.

Constitution Day

A Day for the Constitution—This one day lesson is specially designed for Constitution Day and offers an introduction, warm up activity, short videos for each of the three activities that can be used independent of one another or combined, and reflection questions for closure.

Grades K–2

The President's Roles and Responsibilities: Understanding the President's Job—As a nation, we place no greater responsibility on any one individual than we do on the president. Through these lessons, students learn about the roles and responsibilities of the U.S. president and their own roles as citizens of a democracy.

The President's Roles and Responsibilities: Communicating with the President—Through these lesson, students learn about the roles and responsibilities of the U.S. president and their own duties as citizens of a democracy.

Grades 3–5

The Preamble to the Constitution: How Do You Make a More Perfect Union?—Archival materials and other resources available through EDSITEment-reviewed websites can help your students begin to understand why the Founders felt a need to establish a more perfect Union and how they proposed to accomplish such a weighty task.

The First Amendment: What's Fair in a Free Country?—This series of activities introduces students to one of the most hotly debated issues during the formation of the American government -how much power the federal government should have — or alternatively, how much liberty states and citizens should have.

Grades 6–8

Before and Beyond the Constitution: What Should a President do?—In this curriculum unit, students look at the role of President as defined in the Constitution and consider the precedent-setting accomplishments of George Washington.

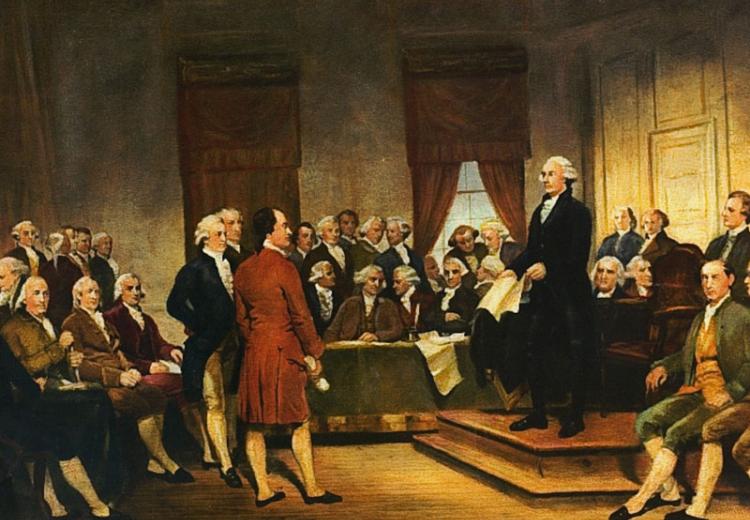

The Constitutional Convention: What the Founding Fathers Said—By examining records of the Constitutional Convention, such as James Madison's extensive notes, students witness the unfolding drama of the Constitutional Convention and the contributions of those who have come to be known as the Founding Fathers: Madison, Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and others who played major roles in founding a new nation. In this lesson, students will learn how the Founding Fathers debated, and then resolved, their differences as they drafted the U.S. Constitution.

The Constitutional Convention: Four Founding Fathers You May Never Have Met—Introduce your students to four key, but relatively unknown, contributors to the U.S. Constitution — Oliver Ellsworth, Alexander Hamilton, William Paterson, and Edmund Randolph. Learn through their words and the words of others how the Founding Fathers created "a model of cooperative statesmanship and the art of compromise."

The Federalist Debates: Balancing Power Between State and Federal Governments—This series of activities introduces students to one of the most hotly debated issues during the formation of the American government — how much power the federal government should have — or alternatively, how much liberty states and citizens should have.

The Supreme Court: The Judicial Power of the United States—This lesson provides an introduction to the Supreme Court. Students will learn basic facts about the Supreme Court by examining the United States Constitution and one of the landmark cases decided by that court. The lesson is designed to help students understand how the Supreme Court operates.

Grades 9–12

Magna Carta: Cornerstone of the U.S. Constitution—Magna Carta served to lay the foundation for subsequent declarations of rights in Great Britain and the United States. In attempting to establish checks on the king's powers, this document asserted the right of "due process" of law. It also provided the basis for the idea of a "higher law," one that could not be altered either by executive mandate or legislative acts. This concept, embraced by the leaders of the American Revolution, is embedded in the supremacy clause of the United States Constitution and enforced by the Supreme Court.

“An Expression of the American Mind”: Understanding the Declaration of Independence—The major ideas in the Declaration of Independence, their origins, the Americans’ key grievances against the King and Parliament, their assertion of sovereignty, and the Declaration’s process of revision. This lesson will focus on the views of the founders as expressed in primary documents from their own time and in their own words.

Slavery and the American Founding: The "Inconsistency Not to Be Excused"—John Jay wrote in 1786, “To contend for our own liberty, and to deny that blessing to others, involves an inconsistency not to be excused." This lesson will focus on the views of the founders on slavery as expressed in primary documents from their own time and in their own words.

The Constitutional Convention of 1787—The delegates at the 1787 Convention faced a challenge as arduous as those who worked throughout the 1780s to initiate reforms to the American political system.

James Madison: From Father of the Constitution to President—Even in its first 30 years of existence, the U.S. Constitution had to prove its durability and flexibility in a variety of disputes. More often than not, James Madison, the "Father of the Constitution," took part in the discussion. Madison had been present at the document's birth as the mastermind behind the so-called Virginia Plan. He had worked tirelessly for its ratification including authoring 29 Federalist Papers, and he continued to be a concerned guardian of the Constitution as it matured.

The Federalist and Anti-federalist Debates on Diversity and the Extended Republic—The proposed Constitution, and the change it wrought in the nature of the American Union, spawned one of the greatest political debates of all time. In addition to the state ratifying conventions, the debates also took the form of a public conversation.

Balancing Three Branches at Once: Our System of Checks and Balances—Attempting to form a more perfect union, the framers of the Constitution designed a government that clearly assigned power to three branches, while at the same time guaranteeing that the power of any branch could be checked by another.

John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, and Judicial Review: How the Court Became Supreme—It is safe to say that as James Madison was the "father" of the Constitution and George Washington the "father of the powers of the Presidency," John Marshall was the "father of the Supreme Court," almost single-handedly clarifying its power of judicial review.

Frederick Douglass's, “What To the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”—Students are guided through a careful reading of Douglass' greatest speech in which he both praises the founders and their principles, and condemns the continued existence of slavery. The Constitution is presented as a "glorious liberty document" which, if properly interpreted, is completely anti-slavery

Abraham Lincoln's Fragment of the Constitution & the Union (1861): The Purpose of the Union—This lesson will examine Abraham Lincoln's brief but insightful reflection on the importance of the ideal of individual liberty to the constitutional structure and operation of the American union.

We the People Teachers- This program created by the Arkansas Humanities Council contains a number of resources and lesson plans for 9th-12th grade classrooms.