The following activities are designed to engage students with the Colored Conventions Project archives, historical newspapers, and consideration of time and place when studying Reconstruction. The activities can be adapted for multiple grade levels and used in connection with other resources provided on this page.

Activity: Mapping Mobilities

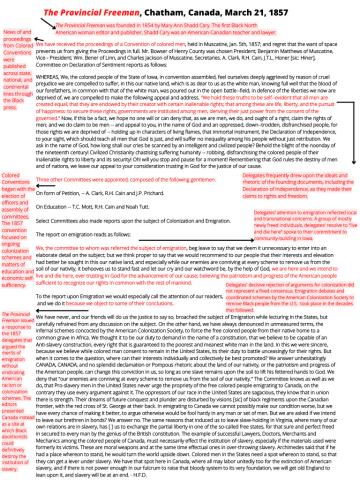

This activity invites students to conceptualize the connections between local conventions and broader developments in the abolitionist and civil rights movements organized across the country. Local newspapers offer a means for tracing these connections. Students will read convention proceedings as they were printed in a newspaper and then contextualize these proceedings in the broader reporting and readership of the newspaper.

Guiding Questions:

-

How did the printing and circulation of convention records contribute to Black institutions and community building?

-

Who were delegates trying to reach as they formulated calls for equality? Who were newspapers trying to reach as they circulated these calls?

Activity: Collaborative Annotation: Contextualizing Conventions

Collaborative annotation is an effective tool to help students draw connections between primary sources and prior knowledge. This activity entails using a free annotation tool such as Perusall, Google Drive, or Zoom Annotation (see Amherst College’s Collaborative Annotation Tools guide for further instruction) to review the convention proceedings included in the document pairings section. Encourage students to underline and highlight dates, names, places, and other aspects of the text that stand out to them for their familiarity or for the questions they raise.

Guiding Questions:

-

Why did Black newspapers choose to circulate calls for and news of conventions?

-

How did the convention movement intersect or interact with the Underground Railroad?

-

How did delegates decide which issues to deliberate? Where did the ideas and language they took up during conventions come from?

Activity: Reading Between the Lines

This activity invites students to expand their sense of the people and places that made up the Colored Conventions Movement. By considering the places and the labor that made the physical gathering space of the convention possible, students will gain a broader understanding of the relationship between community organizing and political action.

Guiding Questions:

-

Who labored to make the visions and demands laid out by convention delegates real? Where did conventions begin and end?

-

How did women’s labor and activism influence the political ends that delegates pursued during conventions?

Activity: Mapping Activist Communities

This activity invites students to contemplate where and how politics have been practiced outside of designated gatherings. Students will read convention proceedings alongside the newspapers in which they were printed. This document pairing will enable students to interpret the convention’s attendance, issues, and demands in the broader context of the community. By considering the relationship between a Black political convention and the community in which the convention gathered, students will gain a fuller sense of how political and social change has been effectuated throughout history.

Guiding Questions:

-

What else was happening in the community at the time of the convention?

-

How did the gathering of a convention affect the rhythms and concerns of everyday life in the community?

-

Who might have read news of conventions in the newspapers?

Case Study: Bethel AME Church in Muscatine, Iowa

The connections between churchbuilding and convention movement histories in Iowa offers a useful case study for rethinking the arc, concerns, and influence of antislavery and civil rights politics. Iowa’s AME churchbuilding and Black political convention movements followed parallel tracks from the 1840s to the end of the nineteenth century. AME churchbuilding in the state began in 1848 when Black Methodists founded Bethel AME church in the river town of Muscatine, Iowa. Just under a decade later in 1857, this church served as the meeting space for one of the state’s first conventions. The churchbuilding and political convention movements overlapped in the following decades, with around twenty congregations and seventeen political conventions organizing by the turn of the century. As was the case for the convention held in Muscatine in 1857, churches often provided the meeting space for conventions, AME pastors presided as convention presidents, and delegates drew upon religious language and rituals as they called for suffrage, citizenship, and education rights.

1857 Muscatine Convention Proceedings

Download pdf of Annotated Proceedings

Guiding Questions:

- To what extent do local historic sites of Black organizing and protest change your view of the history of slavery, emancipation, and Reconstruction in the United States?

-

What people, organizations, and causes intersected in their struggle to end slavery and secure Black freedom?

-

How did these different groups of abolitionists and freedom strivers diverge in their philosophies and strategies?

Resources:

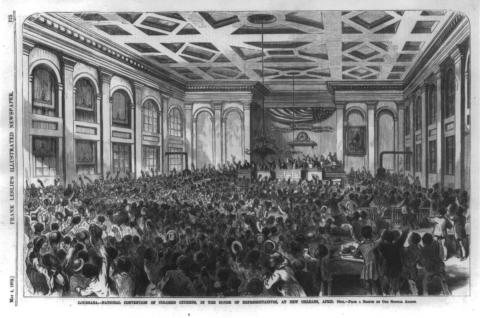

The Meeting That Launched a Movement: The First National Convention: This CCP exhibit examines the 1830 gathering at Philadelphia’s Mother Bethel AME church that is considered to be the inaugural Colored Convention.

Brief History of Mother Bethel A.M.E. by Richard Newman: In this video, scholar Richard Newman introduces the history of the Mother Bethel AME church while leading a tour of its surrounding neighborhood.