Poinsettias, Posadas, Piñatas, Pathways of Light! Holiday Traditions from Mexico

A poinsettia flower

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. By André Karwath aka Aka - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16584

"¡No quiero oro, ni quiero plata, yo lo que quiero es romper la piñata!"

“I don’t want gold, I don’t want silver, all I want is to break the piñata!”

—Traditional Mexican rhyme sung during fiestas, like the posadas, when piñatas are broken by attendees.

When the Spanish Europeans came to America, they were introduced to the culture, art, and agricultural products native to the Americas. Likewise, indigenous people in what is now Mexico were exposed to many practices from Europe that were new to them, as well. This December, EDSITEment invites students and teachers to celebrate this encounter between the Old and New Worlds by discovering holiday traditions from Mexico!

Mexican National Holidays

The Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe (Día de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe) is a Catholic celebration observing the appearance of the Virgin Mary to an Indian man in the first years of Spanish rule. This holiday continues to be celebrated by Mexicans and Latinos in many countries every year on December 12. Mexican Culture and History through Its National Holidays, Activity 2. Día de Nuestra Señora De Guadalupe explores the historical as well as religious context of this festival including online videos and images of the Basilica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe on the visitation site. Mexican Holidays is a companion resource where students discover additional celebrations and historical moments an interactive learning experience.

Poinsettias: “La flor de Nochebuena”

December 12 also commemorates the poinsettia — the most popular holiday plant, which is indigenous to Mexico and Central America. December 12 has been officially designated by the U.S. Congress as National Poinsettia Day in honor of the first Ambassador to the new Republic of Mexico, Joel Poinsett, as well as of American businessman, Paul Ecke Jr., who later successfully marketed the poinsettia worldwide.

Historically, Mexicans have conveyed the symbolic significance of poinsettias by displaying them at holiday time. During the 17th century the poinsettia became known as “La flor de Nochebuena” (Holy night flower). Franciscan priests observed this flower blooming naturally in the fall, a herald of the Christmas season. They incorporated it into Nativity processions, such as the Fiesta of Santa Pesebre. Earlier, the Aztecs cultivated the poinsettias for its reddish-purple color in order to create dye as well as a medicine that would counteract fever. Poinsettias, known as “cuetlaxóchitl” (star-flower) in the Náhuatl (Aztec) language family were held sacred by the nobility. Prized for their intense red color, a symbol of purity, poinsettias played a part in the traditional religious ceremonies. Learn more about the Aztec civilization by accessing, Aztecs: Mighty Warriors of Mexico and Aztecs Find a Home: the Eagle has Landed. Discover how the Aztec Empire fared in its encounter with the Spanish via this EDSITEment-approved website, Conquistadors.

In modern times the poinsettia is regaled everywhere as a ubiquitous sign of Christmastime. Interestingly enough, an annual post-season NCAA sanctioned college football bowl game, which takes place in San Diego, is known as the Poinsettia Bowl according to the Poinsettia Fact Pages from the University of Illinois Extension.

Posadas

In addition to the poinsettia, a number of other customary holiday practices have entered American culture from Mexico, many with religious significance reflecting the Catholicism inherent in this culture. Traditional posadas, a word meaning lodges or inns in Spanish, are held over nine days by communities each year from December 16 through December 24. In these posadas, also known as “Los Peregrinos, San José y la Virgen María,” participants re-enact the experience of Mary and Joseph seeking lodging on their trip to Bethlehem.

Anthropologists have traced the origins of posadas back to the ancient holy pyramids of Teotihuacán. Similar to the tradition of caroling, participants spend the evening going door to door through the community holding candles and singing to ask for shelter at every house, school, and business. At the end of the singing of the posadas, the people who answer the travelers from inside the house open the doors to symbolically welcome them to spend the night, saying, “Entren santos peregrinos, peregrinos” (“Enter holy travelers, travelers”). The carolers enter the house to find a feast which begins with traditional cuisine of the season, including tamales and ponche.

Piñatas

Another whimsical, well-known holiday practice involves las piñatas, colorful hollow figures made of crêpe, tissue paper, or papier-mâché with a clay interior where sweets are hidden. During a fiesta, such as a birthday party or a posada, children and even adults are blindfolded and take turns hitting the piñata with a stick in an attempt to break the clay container to get the sweets out. The piñata hangs from a rope with two people holding each end, which allows for the piñata to be moved unpredictably while the spectators sing and clap. Piñatas can be of any shape, or look like any character or theme from popular culture. The breaking of the piñata is accompanied with this jingle, “Dale, dale, dale, no pierdas el tiro, porque si lo pierdes, pierdes el camino” (“Hit it, hit it, hit it, don’t lose your aim, because if you lose your aim you’ll miss the road”). During traditional celebrations, like the posadas, the traditional piñata will usually be in the shape of a seven-pointed star with a variety of bright colors (though they also come in nine and five points). Each point represents what some Christians believe to be one of the seven deadly sins, or seven capital vices. Beating the piñata is a symbolic act that implies killing the sin and starting anew with the birth of the Christ child.

Another whimsical, well-known holiday practice involves las piñatas, colorful hollow figures made of crêpe, tissue paper, or papier-mâché with a clay interior where sweets are hidden. During a fiesta, such as a birthday party or a posada, children and even adults are blindfolded and take turns hitting the piñata with a stick in an attempt to break the clay container to get the sweets out. The piñata hangs from a rope with two people holding each end, which allows for the piñata to be moved unpredictably while the spectators sing and clap. Piñatas can be of any shape, or look like any character or theme from popular culture. The breaking of the piñata is accompanied with this jingle, “Dale, dale, dale, no pierdas el tiro, porque si lo pierdes, pierdes el camino” (“Hit it, hit it, hit it, don’t lose your aim, because if you lose your aim you’ll miss the road”). During traditional celebrations, like the posadas, the traditional piñata will usually be in the shape of a seven-pointed star with a variety of bright colors (though they also come in nine and five points). Each point represents what some Christians believe to be one of the seven deadly sins, or seven capital vices. Beating the piñata is a symbolic act that implies killing the sin and starting anew with the birth of the Christ child.

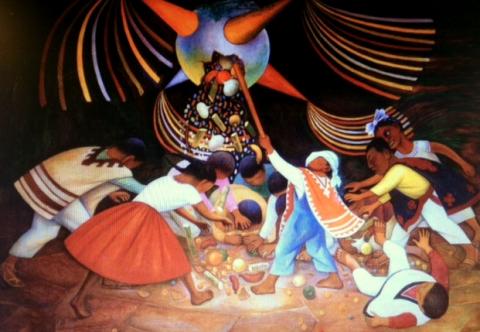

Historically, this tradition was used by the 16th century Spanish missionaries to North America to make religious rituals more appealing. However, similar practices were already performed by the indigenous peoples of Mexico during the winter solstice in the holy sites of Teotihuacán. Aztec priests already celebrated the birthday of their most important deity with a decorated clay pot filled with tiny treasures that was meant to be broken in order to have the offerings fall to the feet of the god, Huitzilopochtli. As with the conversation of pagan societies to Christianity in late antique and early medieval Europe, this may explain the adoption of foreign traditions similar to some indigenous ones. Piñatas later came to symbolize Christian virtues: charity represented by the treats inside the piñata; faith symbolized by the blindfolded individual hitting the piñatas; and hope, represented by the piñata itself—and at which spectators gaze towards the heavens.

Nowadays, piñatas are incorporated into the mainstream of American life, becoming a staple of birthday parties and other celebrations across cultures. Note that the traditional treats included oranges, peanuts, and pieces of sugar cane, though today, a variety of candy and small toys are the favorite fillers.

Luminarias

Another holiday custom from Mexico, widely practiced by communities in Southwestern United States, is the practice of creating pathways of light known as las luminarias, or los farolitos in the weeks leading up to Christmas Eve. The New Mexico History Museum offers a little history on the legend of the luminarias. This tradition has its origins in the 16th century. It harkens back to the Spanish tradition of lighting bonfires in churchyards and roads to guide people to the church for midnight mass, known as “Misa de Gallo” (“Rooster Mass”)—based on the belief that the only time a rooster crowed at midnight was when the Christ child was born.

Another holiday custom from Mexico, widely practiced by communities in Southwestern United States, is the practice of creating pathways of light known as las luminarias, or los farolitos in the weeks leading up to Christmas Eve. The New Mexico History Museum offers a little history on the legend of the luminarias. This tradition has its origins in the 16th century. It harkens back to the Spanish tradition of lighting bonfires in churchyards and roads to guide people to the church for midnight mass, known as “Misa de Gallo” (“Rooster Mass”)—based on the belief that the only time a rooster crowed at midnight was when the Christ child was born.

Today, luminarias involve lit candles placed inside brown paper bags with sand lining to decorate walkways during the Christmas season. Luminarias as a symbol of welcome have also been integrated into mainstream American culture, though this custom is most often practiced in New Mexico. Bring this luminaria making tradition into the classroom, direct from the Hispanic Southwest!